Is Mike DeWine Responsible for the Springfield Migrant Crisis? "Unfortunately, No"

BY MATT URBAS

This Article Was originally posted Here

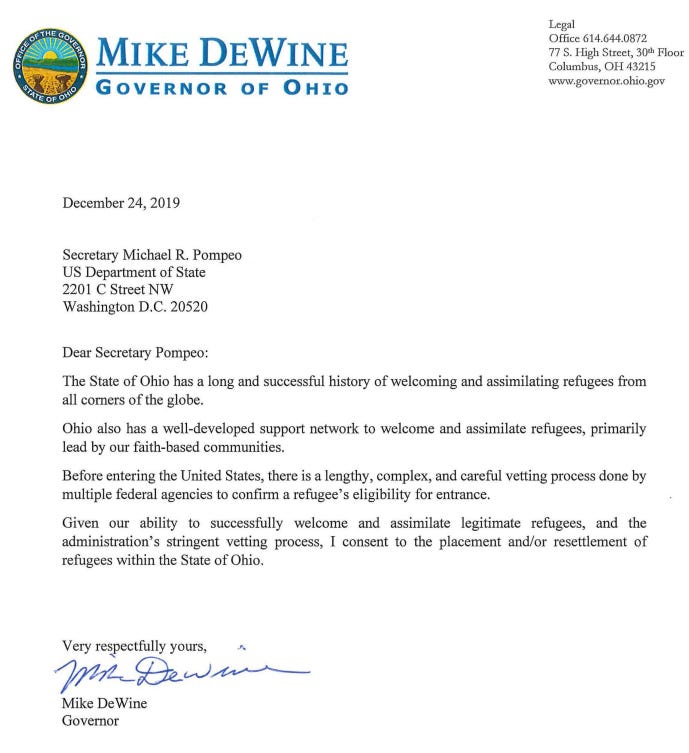

A letter dated December 29, 2019 from Mike DeWine saying that he consents to the placement and resettlement of refugees in Ohio is making the rounds on social media, and his past and future political opponents Jim Renacci and Joe Blystone are using it to do what everyone is doing with the Haitian migrant crisis in Springfield, Ohio: attempt to score political points.

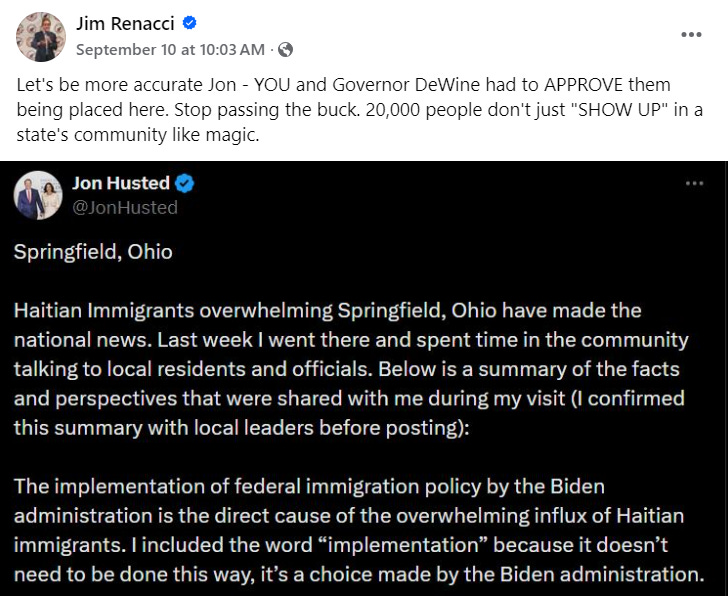

Renacci, who lost a primary challenge to DeWine for the governor’s seat in 2022 and is expected to run for governor after DeWine is term-limited out in 2026, took to Facebook to blame the DeWine-Husted administration for the crisis. Addressing an X post by DeWine’s Lieutenant Governor Jon Husted, Renacci wrote: “You and Governor DeWine had to APPROVE them being placed here.”

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribe

Blystone, who finished third in the 2022 Republican primary for governor and is barred from running for office but maintains his “Blystone for Ohio” page on Facebook, explicitly referred to the letter in a post, saying “Well Ohioans, right here is the unilateral declaration by Governor DeWine!”

The entire reason I started getting into politics was to figure out a way to stop Mike DeWine's COVID-19 policies in 2020 and beyond. I loathe the man with the heat of a thousand burning suns and if there’s something bad happening in Ohio I’d love nothing more than to point the finger at him.

But very soon after I started learning the basic ins and outs of Ohio government and scratching deeper, my purpose very quickly became to learn as much as I could about the problems we have and help Ohioans do the same. I believe an educated populace will create better government. And citing this DeWine letter as if it lays blame on the governor the situation in Springfield today is either ignorant or willfully misleading. “Why Haitians, though?” is a question many readers will have, given DeWine’s connections to the impoverished island nation. But that deep dive is beyond my current ability to investigate – for now please join me on this amateur crash course in immigration policy.

Not all refugees are Refugees.

The DeWine letter that “consent(s) to the placement and/or resettlement of refugees in Ohio,” is addressed to then-president Donald Trump’s Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. It is in response to Trump's Executive Order 138881, which tweaked the operation of the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program by requiring states and/or localities to inform the federal government in writing that they would accept resettled refugees in their jurisdiction. The order instructed settlement agencies to refrain from resetting refugees in places that did not respond that they are willing to accept them.

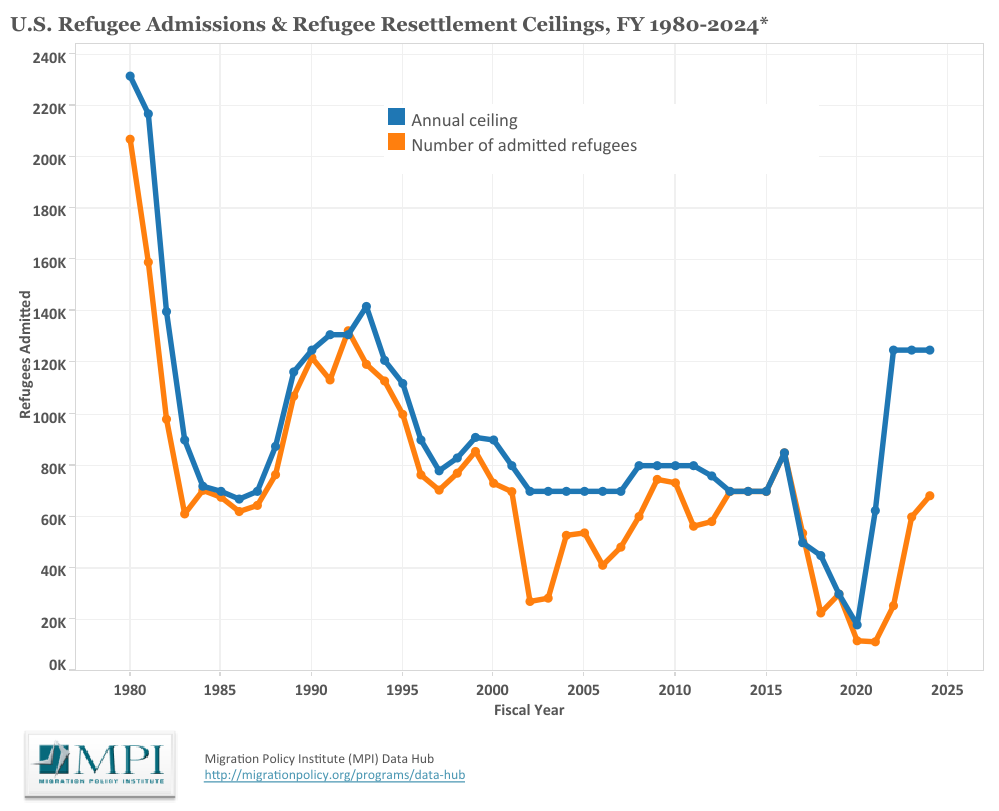

It's important to note that "refugee" has a legal meaning, and that Trump's executive order (and DeWine’s response to it) only concerned the legal definition of legal refugees. Refugees under United States law are individuals in another country who are "unable or unwilling" to return to their home country due to fear of persecution for a variety of reasons2. U.S. law requires the president to designate the number of refugees the country will admit each year. That maximum number of admissions varied between 85,000 and 90,000 under the Bush and Obama administrations, but declined in each year of the Trump administration, and was set at 18,000 for 2020.

There is also a distinction between legal refugees and asylum seekers in that refugees are generally not already in the United States. Individuals who are already in the US and fear persecution in their home country apply for asylum. Refugees are those not yet in the United States, but are seeking settlement here. Both refugees and those granted asylum can apply for a green card after 1 year in the country3.

To sum up: Trump both reduced the number of refugees that could be admitted to the United States per year, and signed an executive order requiring states to say whether or not they would accept the refugees. Under DeWine, Ohio was one of 37 states that responded saying they would accept refugees4. That is the letter we see making the rounds on social media. DeWine was simply saying, "Yes we will continue to resettle refugees in Ohio."

A Short-Lived Policy

The policy of asking states to put in writing that they wanted to accept refugees did not last long. Within 100 days of taking office in 2021, the Biden administration issued Executive Order 14013, which effectively revoked Trump’s order. The Biden-Harris regime also immediately raised the ceiling of refugee admissions and by its second year in office the ceiling was set at 125,000, higher than it had been since 1993.

At this point it’s worthwhile to note that Haitians represent a tiny fraction of the the actual refugee admissions to Ohio anyway. In other words, while in common parlance you will hear the Haitians in Springfield and elsewhere referred to as “refugees,” they are not refugees in the legal sense of the term. In fact recent data shows that only 230 Haitian refugees were admitted to the United States in the last year. There have been 3,188 total refugee arrivals in Ohio with the largest number (1,217) coming from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Only 1 of the Ohio arrivals was from Haiti.

Given the raw data and these facts, I can only conclude that the vast majority Haitians arriving in the US and settling Ohio are NOT refugees under the law. Some may have entered the US and sought asylum, but an alternative for Haitians and many other foreign nationals is something called “Temporary Protected Status”.

Temporary Protected Status

While asylum is an individualized status that must be proven on a case by case basis, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is given as kind of a blanket legal status. The Secretary of Homeland Security is authorized to designate a country for TPS for periods of 6 to 18 months when armed conflict, natural disasters or other "extraordinary and temporary conditions" occur, making it unsafe for those in America to return. If you are a foreign national of one of those countries and are in the United States, you are eligible to apply for Temporary Protected Status. TPS generally gives the holder the ability to live and work in the United States for the period of the designation. The Department of Homeland Security may also extend the duration of the status and re-designate a country for TPS. A re-designation means that individuals who have come to the US since the original designation are eligible to become protected as well.

When “Temporary” is just a word

Haitian foreign nationals in the US were given Temporary Protected Status after the 2010 7.0 magnitude earthquake that struck near Port-au-Prince. The designation lasted the maximum allowable 18 months, but the status was subsequently extended, repeatedly, until May 2017 when Department of Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly announced a limited extension of the TPS, alerting affected Haitians that they should begin preparing documents and making necessary arrangements for return to Haiti. Kelly was named White House Chief of Staff in July, and in November of 2017, acting Department of Homeland Security Secretary Elaine Duke announced that the Haiti’s designation for Temporary Protected Status would end in July of 20195. This was part of a series of terminations of TPS designations for a number of countries including Sudan, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Nepal, and Honduras.

However, legal challenges were mounted challenging the termination of TPS status, on both administrative grounds and that the decision violated the Equal Protection Clause. In granting a preliminary injunction against the Trump DHS decision, US District Court Judge Edward Chen noted that “President Trump harbors an animus against non-white, non European aliens.”6 Ongoing litigation held the the issue up in the courts beyond the end of Trump’s term.

In 2021, Biden DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas announced a new TPS designation for Haiti due to "serious security concerns, social unrest, an increase in human rights abuses, crippling poverty, and lack of basic resources, which are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.7" The DHS estimated that 155,000 Haitians would be eligible to either apply or re-apply for Temporary Protected Status under the new designation8, covering individuals who had been in the US since the 2010 earthquake. The designation was extended for 18 months again in December 2022 with an estimate that an additional 105,000 Haitians would be eligible. As of March 2024, there were 200,005 Haitian nationals with Temporary Protected Status in the United States, and their status was reauthorized in June of this year for another 18 months, with an estimated 309,000 Haitians newly eligible to apply. The latest designation will last until February 3, 2026.

Aliens with Temporary Protected Status in Ohio

The United States Citizen and Immigration Services reported about 12,800 individuals with approved Temporary Protected Status and an Ohio residence as of March 31, 2023. When we compare this to the commonly cited figure of 20,000 Haitians in Springfield, we must remember:

- The 20,000 figure is not just a right-wing talking point pulled out of thin air. Springfield’s city manager Brian Heck stated in a letter to Senators Sherrod Brown and Tim Scott that “Springfield’s Haitian population has increased to 15,000-20,000 over the last four years.” Note that he said “increased to,” not “increased by.”

- Not every Haitian in Springfield qualifies for or has successfully applied for and maintained Temporary Protected Status.

So why might a Haitian with access to blanket legal status in America protecting them from deportation and enabling them to work here NOT apply for it?

CHNV Parole - The Real Culprit?

CHNV parole is a process that the Biden-Harris Department of Homeland Security unilaterally instituted without Congressional approval, where foreign nationals from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela can, if they have a “supporter” in the United States willing to complete a form online, gain legal entry into the United States. Supporters can be virtually anyone legally in the United States, and can in fact be “organizations, businesses, or other entities”9. The supporter completes an application form and then, once the supporter and the individual go through a ‘vetting process’, the foreign national is able to obtain legal entry into the United States for a “parole” period of up to two years. These parolees can obtain employment authorization and a Social Security number. This process was instituted for Venezuelans in 2022 and capped at 24,000 parolees for the year, but expanded in 2023 to offer parole to 30,000 per month from those four countries, or 360,000 per year. The Center for Immigration Studies reported that by June 2024 over 460,000 foreign nationals had been admitted though the program10.

The system is so vulnerable to fraud and exploitation that DHS paused the program in July after “large amounts of fraud were unearthed in applications for those sponsoring the applicants.” An internal investigation by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) obtained by watchdog group Federation for American Immigration Reform found over 100,000 forms were filled out by a set of over 3,000 “serial sponsors”, i.e. individuals with the same Social Security number who completed 20 or more forms11. The Washington Times reported that USCIS put out a call for volunteers within the department to help vet the sponsor applications12 and the USCIS webpage for the program says they have resumed processing applications13.

Such a system is ripe for abuse and human trafficking. Given the sums of money paid by desperate individuals to facilitate travel from Central America through Mexico and across the U.S. southern border, what premium would a Venezuelan or Nicaraguan migrant be willing to pay to bypass that travel in exchange for the application of a “supporter” in the United States that would enable them to fly directly into America? Todd Bensman of the Center for Immigration Studies conjectures:

If a Nicaraguan national were willing to pay $15,000 to take a month-long trip in the hands of a de facto criminal (and potential murderer or rapist), one could ask, wouldn’t they prefer to pay a similar or greater amount to a “supporter” in the United States to start a process that would allow them to come in by simply boarding an airliner to Miami?

Of course, not everyone in one of those four countries has the money to pay the supporter upfront, so it is possible — if not likely — that many of those beneficiaries would agree to work to pay off that money once here….

I trust you won’t be surprised to learn that it is not uncommon for such shady employment agreements to devolve quickly into debt bondage. The trafficker provides housing, which ups the amount owed, and then food and clothing, which adds to the tab. Soon, trafficking victims are trapped in a debt spiral from which they cannot escape, and the terms become more onerous.

Bensman reminds his readers that there are virtually no requirements to be a “supporter” of one of these migrants. A business is allowed to be a supporter:

Own a slaughterhouse in Alabama or a massage parlor in Philadelphia? You, too, can be a "supporter".

Or, as we can all imagine, any number of businesses in the forgotten recesses of small-town Ohio.

https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/asylum-or-refugee-status-who-32298.html

https://2017-2021.state.gov/state-and-local-consents-under-executive-order-13888/

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2024/aug/25/department-of-homeland-security-eyes-restart-of-fr/